As I was writing before, there is also a park close to the Triumphal Arch, which is called Mihail Park after King Michael of Romania. He was the last king of the country who was forced by the communist party and the Soviets to resign, then he fled, lost his citizenship and was living in an exile for most of his life.

Actually, justice reached him finally, because he outlived the communist regime and returned to Romania where an extremely huge crowd greeted him, and even got back his citizenship in the end of his life, although he could never be a king of his country again.

The park is also known as Herăstrău Park due to Lake Herăstrău – a beautiful watery world in the focus of the park. I had already seen it in the map that Bucharest has plenty of lakes as a heritage of the swamp area where it was established, but it was much more fabulous in reality.

There were some boat stations and it was interesting to see me that the tourist ships are called vaporașul in Romanian – it is obviously the Romanian version of vaporetto which I know very well from my Venetian days.

The park was very special for many reasons and gave me a brief introduction to Romanian folklore.

For example, not so far from the Royal Residence (members of the Romanian royal family still own the title) I could see a Village Museum including many wooden buildings designed in the style of Maramureș region (in Hungarian: Máramaros).

However, the biggest surprise for me at the entrance was to see a wooden gate that exactly looked like our Székelykapu (Szekler’s Gate) from Transylvania, which was such a shocking discovery for me like to learn it in Slovenia through Kurentovanje of Ptuj, that Busójárás is not exclusively Hungarian either, but there are similar traditions all around the Balkans.

Same with this wooden gate: apparently it’s a common heritages between Hungarians (Szeklers) and Romanians in the Transylvanian countryside, although the traditional motifs, carvings and working techniques can be different.

The official entrance is from the street side with an enormous, little but vanguardist statue of charismatic French president Charles de Gaulle (a tribute to French-Romanian relations most probably), and then there is a long open hall of columns with fountains and flowers everywhere called Fântâna Modura.

The most genius artistic solution for me was that the caryatids were dressed up as Romanian peasant women holding jars on the top of their heads as it used to be common in the rural life before. By the way, where you can see the statue of de Gaulle today, there used to be a statue of Stalin in the communist times.

I should also recommend the Island of Roses (Insula Trandafirilor) where you will find many huge statue-heads around a round monument: if you look at the twelve stars, you might have a clue that it is connected to the European Union, and indeed, it recalls the most important European Politicians such as Konrad Adenauer, who were putting effort in creating a united Europe.

I could not go there, but the City Gate Towers were also nearby: two office houses imitating a medieval city gate with their arrangement.

There are other statues here and there, like the one of Prometheus, Hercules and the Centaur or Venus from Greek mythology and various animals (a turtle, a turkey, a chamois, a goose), but the most common was to see busts of famous artists and people everywhere.

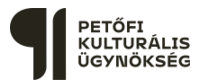

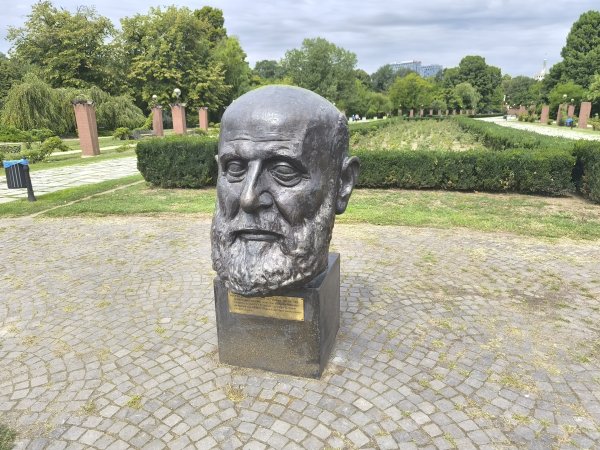

Among them I identified Shakespeare, Twain, Chopin, Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky, da Vinci, Goethe, Beethoven, Botev, Hugo and Darwin, but to my surprise, I also found a statue of legendary Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi and composer Béla Bartók, while there was another one of poet Endre Ady I did not see finally.

A stone monument with folklore motifs also taught me something interesting: it was dedicated to Romanian folklore hero Făt-Frumos ('Prince Charming') who also inspired Mihai Eminescu, one of the most recognized Romanian poets.

I immediately found the relationship between such romantic trends in the region, because Petőfi wrote his epic poem János vitéz ('John the Valiant') a bit earlier in the same century. The fact how many similar literary movements connect us in Easter-Europe just impressed me utterly.

A last thing I would like to tell you about Romanian folklore is my experience from the Museum of the Romanian Peasant (Muzeul Național al Țăranului Român) close to Kiseleff Park and the Victory Square, where you can admire the huge diversity of different ethnographic regions within Romania.

The museum is also the direct neighbor of the Museum of Natural History, which is full of skeletons and models of ancient and contemporary animals.

The facades and the shape of the museum building are pieces of art even regardless the function, and it rather reminded me to a big maison of a rich person than to a typical museum from the outside.

Unfortunately, it was a bit disappointing that most exhibitions were temporarily closed due to some renovations in the building, but still, there were many pots, woven textiles, working tools and dresses recalling the old days of rural life.

It is important to mention historian and ethnographer Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș, because without his work, research and legacy the Peasant Museum would never have come to life.

Many items were originally parts of his collection, especially the most famous exhibited piece, Casa Mogoș: the old wooden house of an Oltenian peasant, Antonie Mogoș, which represents a unique and traditional architecture from the Carpathian mountains.

The scientists learnt a lot by getting know and studying Mogoș and his family, and when the old man wanted to deconstruct his house in order to move to a modern brick building, Tzigara-Samurcaș, who thought that this would be a loss for the cultural heritage, bought the house instead.

Just like for instance the houses of the Opole Village Museum in Poland, the Mogoș house was dismantled and taken then to the capital and has been erected in various places until got its current place in a room of the museum, where it is even furnished according to the living habits of its time.

Finally, we have arrived to the point when we can talk about entertainment and night life a little bit. Bucharest, just like our Budapest is a never-boring, never-sleeping city. Maybe the capacities are more limited in Budapest, but it also includes a lot of additional opportunities.

You can always find a bar, tavern, pub and so on in the narrow streets of Centrul Vechi, the old town, which indeed has a medieval Eastern-European atmosphere when you walk among town houses on paving stones.

The best part to begin according to me is from Rome Square with the Lupa Capitolina and Pasajul Latin I have mentioned before, near the Church of St. George.

From the direction of the Boulevard go directly to Strada Lipscani (Leipzig street), where you will also see some further references of the imfamous and merciless Wallachian prince, Vlad, the Impaler, and legendary taverns like Manuc’s Inn, that exists since the 19th century, and was so important that the Treaty of Bucharest finishing the Russo-Turkish war was even signed there.

As an advanced traveler and as someone who is a man and is tall, most probably I have different experiences that another person would get, but I really felt that the city was safe even at night.

The distances are a bit longer than in other cities, but the public transport, at least bus and metro lines are fast and reasonable and you can use them without any troubles. The only disadvantage of this area is the fact that the places are more commercial and sometimes too international, but if you do some research or ask locals, you will surely find something you like.

At this point I usually tell you what to eat or drink, but this time unfortunately I did not have the chance to find a place where I could really meet the Romanian cuisine, although I gathered some information about it.

Most of the meals have at least one look-a-like in other countries of the region, either in the Balkans or in Eastern Europe, such as sarmale: a sort of stuffed cabbage roll (like Hungarian töltött káposzta or Polish gołąbki), but it's slightly different due to the fact that it is covered with vine leaves instead of cabbage.

Fortunately, I had the chance to try this dish prepared by a Romanian acquaintance for the Orthodox Easter when it is typical to eat, so I know how it tastes like and eventually I did not have to leave Bucharest without trying a local food. Even if I had tried it before this trip.

Mici (‘little ones’) is another popular meal made of meat, which is grilled or fried and is similar to ćevap, kebab and so on.

In terms of alcoholic spirits, there is vișinată, which’s name most probably derives from Slavic languages, because it contains cherries, and there is also palincă.

The name comes from Hungarian pálinka, but in fact, it is not exactly the same distillate drink and it is not used everywhere as a word – in some places, it is called rachiu, similarly to Southern-Slavic spirits.

There were even debates about this issue between the two countries who has the right to claim pálinka, but the international decision cut the Gordian Knot, because the Hungarian spelling became a so-called hungarikum (a trademark or traditional product with Hungarian origin) and the Romanian spelling refers only to the Romanian version of the drink.

We can also mention țuică, a similar spirit which is particularly distinguished due to the fact it is made of plums.

Now we have come to the end of a chapter, but Bucharest was not everything I discovered in Romania, so it is not the time for an evaluation yet. I am rather inviting you to join me next time and visit the marvelous Black Sea together!